One hundred years ago, the German architect Walter Gropius decided to establish a school that would adapt art to society’s needs. The Bauhaus covered all disciplines of design, from industrial design to furniture design, as well as the creation of other objects in its metal, carpentry, ceramic, and textile workshops. It also covered pictorial and sculptural art and, of course, architecture. Today, we are taking a look at the history of functional architecture that came out of this artistic movement that shunned embellishments and which continues to be an international benchmark.

Gropius House, Lincoln, Massachusetts, 1938

Gropius House, Lincoln, Massachusetts, 1938

Weimar, the origin of the Bauhaus

The name of the school came from the combination of the German words for construction (bau) and house (haus). With this name and an architect as its founder, it was inevitable that it would contain architectural studios. However, construction was always just one of the fields it covered, as seen in the Haus am Horn (1924), the only remaining legacy of the school in the city.

This “model” or “experimental house” was built to satisfy all the needs of a citizen of the times and contains all the architectural principles of the Bauhaus: streamlined shapes (squares and rectangles), without any frills, and a structure that can be built with few resources and using novel materials. Inside, it had the most advanced technology of the time, like central heating and a laundry, and furniture made in the school’s workshops. This white cube was supposed to be the first of many which would house students and teachers, but these were never completed due to the school’s relocation.

Haus am Horn, Weimar, 1924

Haus am Horn, Weimar, 1924

Dessau, the splendour

In 1925, the school had to be moved to Dessau. Gropius decided to take advantage of the opportunity to create a building that would embody the Bauhaus principles. It was the authentic Gesamtkunstwek, a “complete work of art”, as the buildings and their interiors were designed as parts of a whole. It was decorated by the students of the mural painting workshop, the metal workshop created the light fixtures, and the letters on the façade were designed by Herbert Bayer.

The complex was made up of different sections that were connected, with each one having its own purpose: one wing was for workshops, another was for teaching, and another was the students’ residence. Its shape was that of a windmill or propeller. For its construction, Gropius used new materials, like reinforced concrete, and innovative construction methods, such as glass curtain walls.

La escuela de Bauhaus en Dessau encarna todos los principios del movimiento

La escuela de Bauhaus en Dessau encarna todos los principios del movimiento

The Masters’ Houses were nearby, including those of Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, Josef Albers, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky. The clean, cubic shapes, large windows, and simplicity were repeated in the buildings’ exteriors and interiors, though they were destroyed in 1945 during the WW2 bombings.

Masters’ Houses, Dessau, 1925

Masters’ Houses, Dessau, 1925

The most complete Bauhaus archive is in Berlin

Berlin, which was home to the school in its final months before the triumph of the Nazis destroyed it, was chosen as the home of the first Bauhaus museum, where products from the workshops, models, plans, photos, and more are on display. The Bauhaus-Archiv is located in a building designed by Walter Gropius which stands out for its distinctive sawtooth ceiling, designed to spread indirect natural light throughout the interior.

It was in 1933, when the school closed its doors for good, that the Bauhaus movement spread all over the world thanks to its exiled teachers and students.

Bauhaus Archiv, Berlin, 1976-1979

Bauhaus Archiv, Berlin, 1976-1979

Tel Aviv, a Bauhaus city

On the run from Nazism, Hannes Meyer, architect and director of the school from 1928 to 1930, arrived in Israel with a large group of students. They then proceeded to spread their architectural style throughout the city. The almost 4000 buildings constructed in the 1930s make Tel Aviv the most Bauhaus city in the world, and it is now called “the white city” thanks to the colour of the buildings’ façades.

Avraham Soskin House, Tel Aviv, 1933. Photo: www.archilovers.com

Avraham Soskin House, Tel Aviv, 1933. Photo: www.archilovers.com

New Bauhaus: Bauhaus in America

The New Bauhaus was key in the continuation of the movement’s spirit and the diffusion of its ideas in the United States. Founded by Moholy-Nagy in Chicago in 1938, the school formed the origins of the famous Illinois Institute of Design that opened in 1949.

But we can also find great examples of Bauhaus architecture in America. Three of is most influential creators settled there: Mies Van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Marcel Breuer. Their modern and functional architecture was a hit with Americans.

Some standouts among the work Mies van der Rohe did in the US are the Illinois Institute of Technology Campus in Chicago (1939-1958), where he was the head of the architecture department, and Farnsworth House (1951), a simple metal structure standing on pilotis and encased in glass, which makes it look as if it is floating in its surroundings.

Farnsworth House, Illinois, 1951

Farnsworth House, Illinois, 1951

Walter Gropius applied the principles of the school to the family home he built in Lincoln, Massacheusetts, when he came a Harvard professor in 1938. The furniture design was put in the hands of his disciple Marcel Breuer, with whom he collaborated with on other projects, such as the Alan IW Frank House (1940) and the Hagerty House (1938).

Breuer dedicated himself to entirely to architecture in the US, where he designed more than 100 buildings, such as Breuer I House in Connecticut (1948) and the current site of the MET Breuer in New York (1966), which is a true building-sculpture.

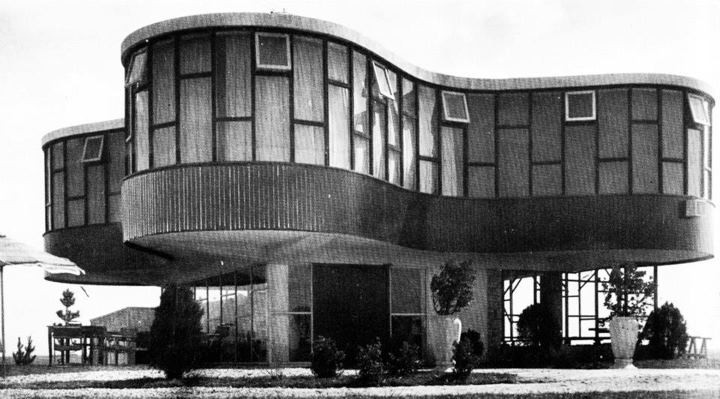

The only example of Bauhaus architecture found in South America can be seen in Argentina and, unfortunately, it has fallen into a state of neglect. The Parador Ariston (1948), built in Mar de Plata by Marcel Breuer, is a structure with one elevated floor and curves inspired by the shape of the clover.

Parador Ariston, Mar de Plata, 1948

Parador Ariston, Mar de Plata, 1948

The Bauhaus in Europe

There’s no need to cross the pond to see the work of the Bauhaus, as the old continent also has great examples of Bauhaus architecture that we can fall in love with during these summer holidays.

One of the first Bauhaus constructions outside of Germany was the Pabellón Barcelona, designed by Mies van der Rohe for the 1929 exposition. The furniture in the interior was also designed by the school, including the iconic Barcelona chair.

Villa Tugendhat (Mies Van der Rohe, 1930), in the Czech Republic, is one of the biggest icons of residential architecture of the 20th century. It’s an integral work, consisting of a glass, steel, and concrete structure which allows for the use of large windows instead of walls. Both this, and the interior, from the furniture to the light switches, were designed or specified by van der Rohe.

Villa Tugendhat, Brno, 1930

Villa Tugendhat, Brno, 1930

Before arriving in the United States, Marcel Breuer spent some time in London, during which he designed Sea Lane House (1936).

Some of the highlights of Bauhaus architecture in France are three works by Marcel Breuer: the UNESCO headquarters in Paris (1951), the IBM headquarters in La Gaude (1962), and the Faline ski station (1969).

UNESCO, París. Photo: unmultimedia.org

UNESCO, París. Photo: unmultimedia.org

The women of the Bauhaus

The role of women at the Bauhaus is a controversial issue. The school was founded upon the philosophy of equality between men and women, as declared by its founder Walter Gropius, who said “there is no difference between the beautiful and the strong gender. Absolute equality, but also absolute equal duties.” However, in practice, women were excluded from the architectural, sculpture, and painting studios, which Gropius considered to belong to males. Women were confined to the field of textile design, as Gropius thought that women were not capable of thinking in three dimensions.

One of the first to rebel was Marianne Brandt, who entered the metal workshop where she became the firm favourite of its director Moholy-Haghy, whom she later substituted. There was also Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, who entered the carpentry workshop, where she stood out for her designs for children that continue to be produced today. She was the inspiration for the protagonist of the film Lotte am Bauhaus, which looked to raise awareness of the role of women at the institution. Publishing house Taschen also released their Bauhausmädels. A Tribute to Pioneering Women Artists, which was an homage to these female pioneers of modernity in a man’s world.